In the past few years, there have been major advances in the development of VR (virtual reality) and AR/XR (augmented reality/mixed reality) headsets and glasses. Especially with Apple’s entry into the headset market, and Meta’s progress in developing viable AR glasses, more and more people are beginning to embrace the idea that an altogether new, and more immersive way of interfacing with our technology is right around the corner. This comes on the heels of Facebook’s rebranding as “Meta”—they insist that they no longer are a social media company, but a “metaverse” company. This announcement drew ire—especially from people who are skeptical about big technology companies. However justifiable people’s skepticism about big technology companies is, it would be foolish to reject the concept of the metaverse altogether.

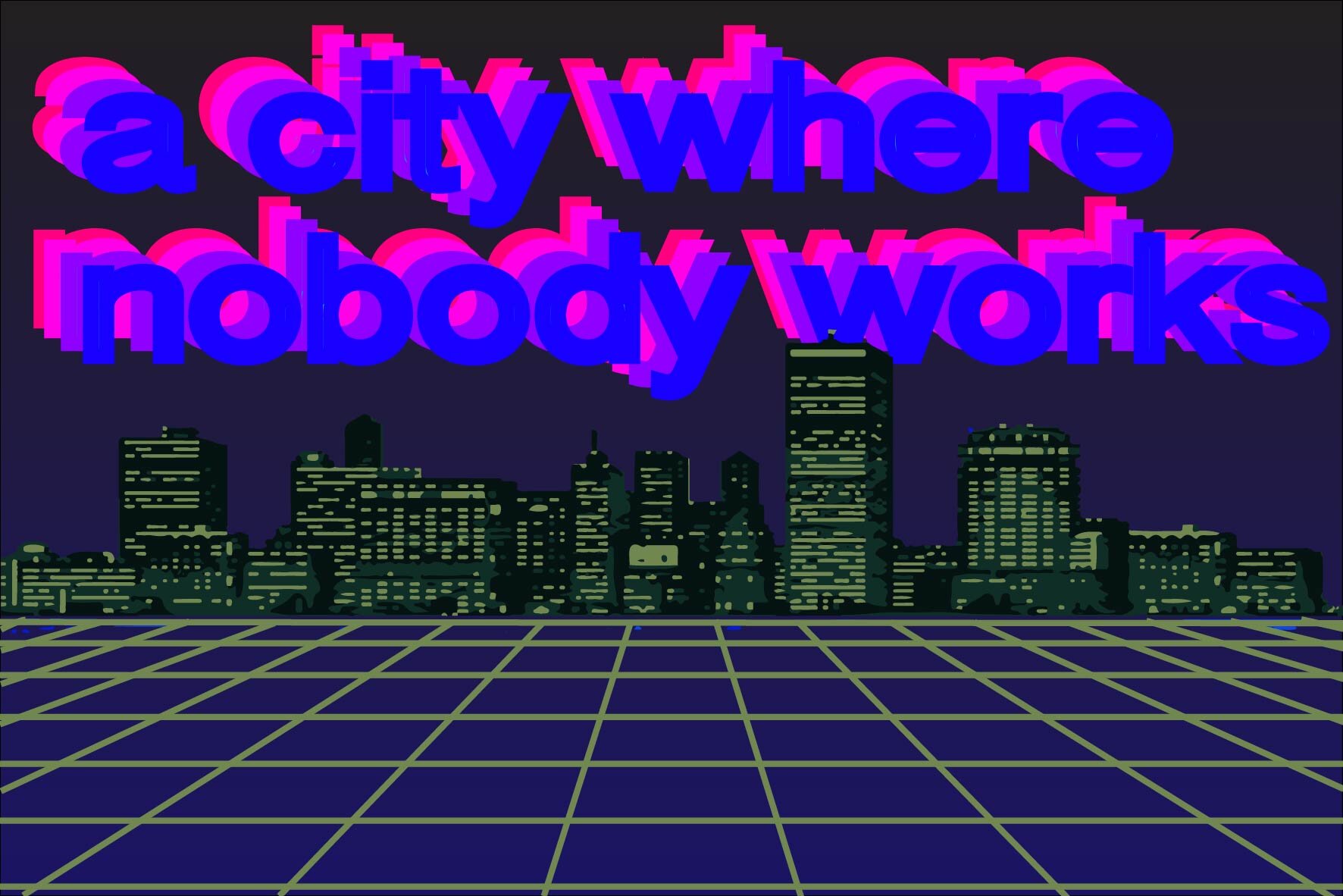

As a number of writers have pointed out, the “metaverse”—the spatialization of digital information and experiences—holds out quite a utopian potential for humanity. By offering a digital sphere in which people can enact their fantasies, build, create, explore and interact without the need for vast amounts of energy or materials, and with few limitations, virtual reality could be the medium within which human beings create some of their greatest and most profound creative expressions and experiences. On the other hand, it could just become an extension of our flawed society—a more effective medium to control and manipulate people with. How can the metaverse be something other than a dystopian extension of social media and a numbing psychological escape from a deteriorating planet and devolving society?

Something I’ve been contemplating a lot lately is the question of how the concept of the metaverse relates to the concept of the pluriverse.

As you’ll likely be aware by now, the concept of the metaverse is fundamentally about the way that digital environments are becoming increasingly immersive—both in terms of their spatial and temporal omnipresence in our lives, and in terms of the ever-advancing interfaces that we use to connect access consoles (Internet-connected devices) to our sensory organs.

The pluriverse is a concept that describes a world composed of many worlds, where many different ontologies (or concepts about and ways of being) are able to coexist. Drawing inspiration especially from the many traditional and indigenous cultures whose ways of being are/were flattened in the twin processes of modernization and industrialization, many advocates of the pluriverse seek to restore “vernacular wisdoms” as a solution to the ecological and sociological crises of that modernization and industrialization process. For advocates of the pluriverse, these vernacular wisdoms should be used to create many worlds, rather than a single, homogeneous one. As the Zapatistas put it, “Queremos un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos” (“We want a world where many worlds fit”).

Generally, those who embrace the idea of the pluriverse are completely disinterested in the promises or politics of the metaverse. The advocates of the metaverse generally position its rise as an apotheosis point of economic and technological development, wherein computers facilitate the rise of some ultimate frictionless, limitless human experience. For them, development can only be a great thing, since it brings about the technological capabilities to create this digital paradise. In contrast, the concept of the pluriverse, deriving as it does from “degrowth” and anti-globalization political discourses, tends to eschew economic and technological development as pathways to many forms of what Ivan Illich termed “modernized poverty,” denoting a slavish dependency on an abusive economy.

Personally, I think that these beliefs are both wrong, in a way. Something that neither viewpoint tends to consider is that perhaps there are—and indeed ought to be—alternative modalities of development. The metaverse’s optimists don’t seem to be realistic about the self-destructive flaws of an economic system that is both crisis-ridden and materially polarizing—tendencies that may ultimately threaten and altogether undermine our ability to create a functioning and sustainable digital utopia.

As anyone familiar with the various fictional depictions of the metaverse (and here I’m thinking of “Ready Player One” and “Snow Crash”) will be aware, the context for the rise of the metaverse concept in these depictions is one of massive economic and political failure and catastrophe. In these stories, the metaverse becomes a digital substitute for a ruined real world. To escape the curtailed freedoms and enjoyment of a world riddled with pollution, overpopulation, dysfunctional economies, and overbearing (and/or corrupt/ineffectual) governments, people seek refuge in a kind of digital oasis of infinite possibility. The point here is that the metaverse, as a concept, has a complex relationship to development. In the first place, the metaverse requires the overcoming of immense engineering hurdles: ubiquitous access to technology; equally widespread high-speed connectivity; massive computational power; the invention, production, and distribution of interfaces that create a fully immersive user experience; and the presumed leisure time to spend inside of a digital reality. And yet, the fictional context of the metaverse is, if anything, one of “overdevelopment.”

As for the pluriversal pessimists, they tend to be a bit too down on development, as if its outcome can only spell extinction and destruction. Marx—who many don’t realize was quite the accelerationist—thought that the utopia of communism could only be reached after a long slog through capitalist development, which would have severe consequences for those who endured the transitional stage. But the transition would not be a smooth, linear one; it would involve crisis and revolution, as an economically-faltering capitalist economy systematically failed to unlock the very prosperity and utopian potentials that it itself made possible. Development, for Marx, was both necessary and insufficient. At some point, political struggle needed to intervene in the process of economic development.

Perhaps an effective way to conceptualize development is in infrastructural terms. Infrastructures change our environments in ways that are simultaneously alienating and empowering. A key dimension of this is the way that infrastructures free us from needing to think or worry about details and logistics that preoccupied cultures that preceded these infrastructures. We don’t often think about the way that terraforming and medical innovations and various grids and networks compose a sort of “second nature” that raises the overall “floor” of human existence by pushing once-insurmountable problems to the peripheries of our consciousness. “Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking,“ the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead claimed. Once a generation of problems are solved, they drop from both our consciousness, and from our aspirational dreams, appearing as a pre-given world within which we move on to bigger and better problems and aspirations. As Sigfried Giedion put it, “Dreams lose their fascination when frozen into naturalistic terms.” When these things work well, we tend to take them for granted.

Something that the pluriverse framework seeks is the freedom of autonomy. Yet autonomy, as Benjamin Bratton insists, must be reconceptualized in infrastructural terms. “[A]utonomy,” he tells us in his book on terraforming, “is less about free will than what aspects of action can be done without full deliberation or even without choice.” The routinization of tedium that used to dominate our consciousness; the taken-for-granted safety and security of worlds and spaces that once were terrorized by disease and/or conflict and/or famine is nothing to be sniffed at. We stand on the largely invisible, infrastructural shoulders of giants. Indeed, our very species, Bratton insists, “is the result of its co-evolution with its ancient automated landscapes.“

This infrastructural way of thinking about development suggests that humans can remake their world(s) in progressive and positive ways. Development can be the process whereby this floor is raised—and it needn’t necessarily involve economic “growth” or exploitation, even if it has tended to do so within our current political economy. I don’t imagine anyone actually begrudges the raising of the “floor”; they begrudge the side effects and externalities deriving from this process. But perhaps the former doesn’t necessarily require the latter.

Before thinking a bit more about how to reconcile these differences over the status of modernity and development, we should explore the many resonances between the pluriverse and the metaverse. Both valorize the plurality and immateriality that we see haphazardly emerging in our world and in our culture.

Plurality is something we all already experience, both culturally and psychologically. Globalization, for all its flaws, has done a lot to accelerate multiculturalism (in the developed “centers” of global capitalism anyway), bringing people from all over the world into regular contact with each other. With the rise of the Internet, we also are increasingly aware of what is occurring in other places, and, despite social media “bubbles,” we are also frequently made to encounter people who are very different from us. As our national cultures—which were always merely partial anyway—dissolve into a vast array of subcultures, our own localities (perhaps even out own families) become increasingly pluralistic, for better (diversity) and for worse (fragmentation and polarization).

This cultural plurality is mirrored in our psychological existences. We increasingly inhabit a highly partitioned digital existence, which takes place in a variety of “containers”—often apps and websites—which hybridize with our physical settings. We all know the experience of carrying on an intimate conversation—perhaps even multiple—while simultaneously navigating transit or an in-person social experience. We also all know the frustrations of distractions—the fragmentation of our own continuity of experience, and that of those in our proximity. Yet, there is something deeply rich and dynamic about connectivity, and switching rapidly between containers of experience and relationality.

I think that the pluriverse should be something that we demand from any putative metaverse. If it’s not a pluriverse—in the sense of empowering multiple ontologies to thrive—then it’s not actually a metaverse. Perhaps by seeking to hybridize metaversal and pluriversal theories and political aspirations, we can begin to imagine alternative forms of development and modernity. An indeed, this is precisely what I think that political metamodernism is doing (though the key authors of this concept are not framing their thinking in terms of its relationship to the metaverse or the pluriverse).

Advocates and theorists of the pluriverse emphasize the importance of the idea of “conviviality”—the virtuous outcome of an operative political philosophy that does not require economic growth to produce prosperity, since prosperity is reimagined in immaterial terms of flourishing social and cultural dynamics and the shared life and joy that these are able to create.

This immateriality has a parallel in the metaverse. At its most utopian, the metaverse promises to valorize immaterial goods such as connection, expression, and experience, rather than remaining tied to material accumulation. Granted, in its more dystopian modality, the metaverse is imagined as a place where material inequalities and hierarchies are reproduced symbolically, through the unnecessarily exclusive ownership of digital assets such as NFTs and cryprographically-secure online “real estate.” Yet, even here, immateriality ultimately reigns. As Andre Gorz pointed out in his final book on the immaterial, perhaps capitalism’s final act will be the desperate (and ultimately fruitless) accumulation of symbols and knowledge, before sharing, zero-cost exchange, and infinite reproducibility render it obsolete once and for all—a prospect that becomes far more likely in a world where culture and sociality occur in the “metaverse.” In this context, while new hierarchies and modes of exclusion are likely to emerge, there is likely to be far more space for social and cultural life to unfold unhindered.

In order to truly be “meta,” the metaverse must actually empower the vast majority of human realities, cultural logics, and practices. It must operate as a kind of grid, or substrate that hosts and powers these many worlds. An important requirement of this meta-infrastructure is that it must be accessible and sustainable, which requires that the cultures and worlds that it hosts must not seek to destroy it or impede others from accessing it. The fictional political metamodernist Hanzi Freinacht, drawing on the “open society” concept of Karl Popper, explains that a functioning metamodernist society can only tolerate cultures that are themselves tolerant of other cultures.

This version of political metamodernism aspires to create a “trans-culturalism” that is simultaneously in favor of societal development and wellbeing while avoiding totalizing and stifling cultural homogeneity. A crucial part of this is establishing a minimum set of rights and duties for all cultures—particularly the demand that they not prevent individuals or other cultures from enjoying full access to the diverse offerings of trans-cultural, metamodern life itself. And what makes this possible is that the underlying political, economic, and cultural infrastructure of metamodernism acts as a kind of enabling/empowering substrate that guarantees material and psychological wellbeing.

In terms of the pluriversal metaverse, the the meta and the plural should keep one another accountable in a productive tension. On the meta side, there should be a guarantee that users—whether they are individuals or groups—be guaranteed the ability to create worlds and partake in cultures, so long as these worlds and cultures do not affect the ability of others to do the same. This is how the “meta” harmonizes the “plural.” And at the same time, the plurality must demand its right to build and inhabit worlds—to have what Arturo Escobar calls “design autonomy”: a full panoply of “tools, interactions, contexts, and languages” that facilitate the creation of ontologies and their worlds. This would constitute an unprecedented degree of freedom. This is the accountability that the plural demands of the meta.

If we demand that the metaverse be a pluriverse, might that demand extend to the physical world as well? In other words, perhaps the many worlds of a pluriversal metaverse would spill out of digital space and into physical space, constituting a new kind of built environment. We already see immaterial logics completely reshaping physical geographies, from data-directed movement patterns to algorithmically-designed spaces and sensor-controlled environmental parameters. Could the metaverse become a new routing switch to physical spaces and places in the analog world? If the pluriversal metaverse contains countless, interwoven “worlds,” perhaps an analog layer of this metaverse would involve a tapestry of different geographical realities; a maze of many urbanisms and their metabolic processes.

Most of the universe is empty space. What’s rare is density and complexity. If one of the things that makes a metaverse (or indeed any human creation) worthwhile is its complexity, then perhaps our goal as a society should then be to build worlds that contain practices that are extremely unique and intense. Places of 24/7 activity; thriving subcultures; profoundly customized rituals and emotional experiences. This is the polyvalent futurism that I believe a pluriversal metaverse can produce.