The following is a prompt delivered at the beginning of a design charrette, where we invited participants to brainstorm and design visions (whether designs, art, or writing) imagining what cities could be like in a pos-work world. The charette was part of a larger project called Imagining the Post-Work Future (in collaboration with Andra Bria), which arose out of a blog post I wrote a few years ago on the topic.

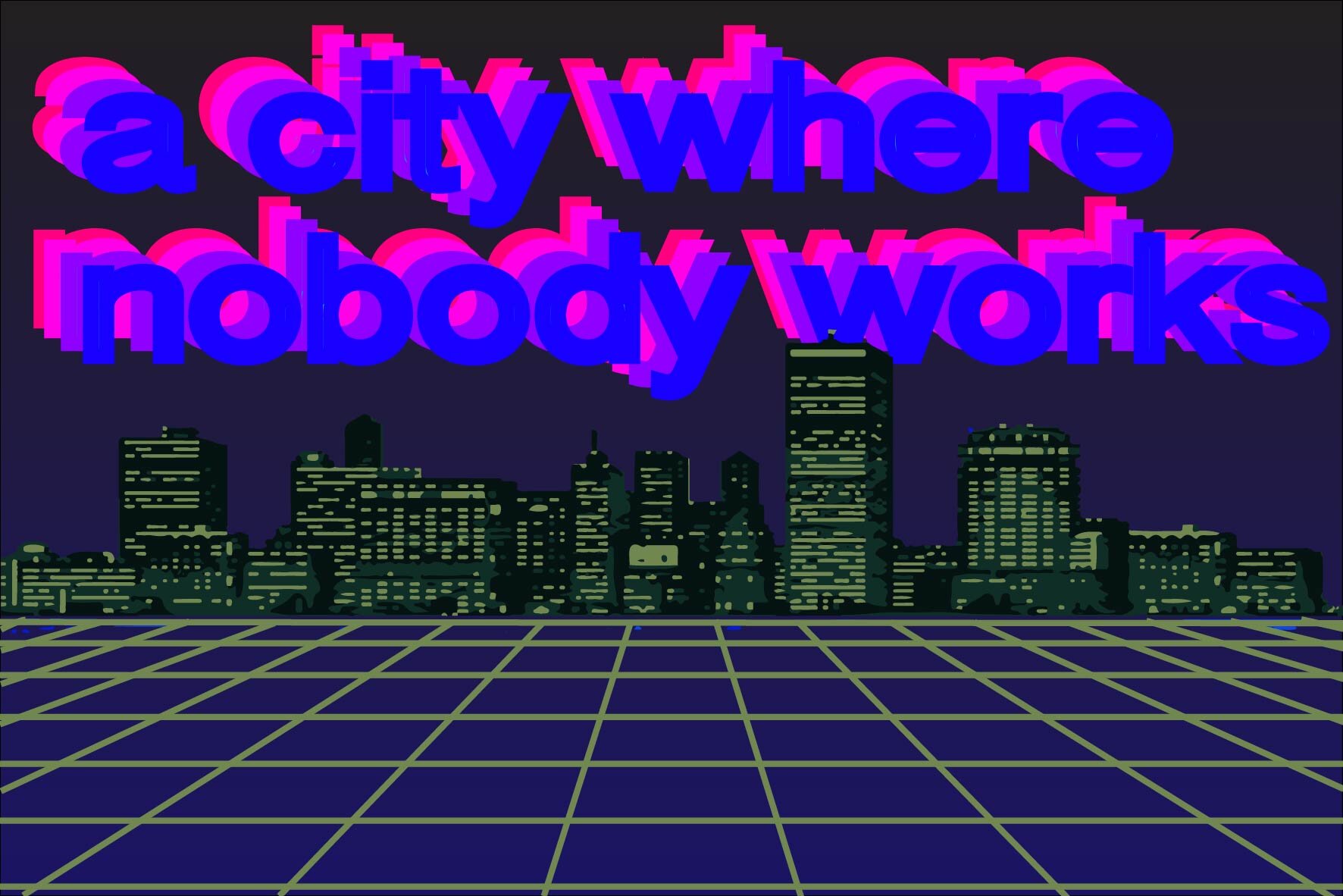

We invite you to imagine and design art and design projects and proposals that envison what cities could be like in a world where we no longer have to work in order to sustain ourselves.

Cities of industry: Such a prospect demands a total rethinking of the existing spatial organization of society, since contemporary cities are designed with one particular universal in mind: the pervasiveness of work. Work has not only dominated our political imaginaries (from so-called “right to work” policies, to political platforms of “job creation,” economic security has tended to be unquestioningly tied to employment), but also the very landscapes in which we live our lives.

“Idleness”: Of course, at the heart of this spatial question is the matter of time: The way people spend time in a society fundamentally shapes the forms and functions that the city must take on and perform. In their present form, cities are plagued with a paradoxical combination of stressful and existentially challenging ways of experiencing time. On the one hand, you have so-called “idleness” among the unemployed and underemployed. This is for those in our society who have lots of time, but no money, and therefore no way of accessing the pay-to-play pleasures of leisure, or paid employment. If you have lots of time and no money, the metropolis is a hollow, cold series of streets, bounded by impenetrable facades, fences, walls and windows.

“Hyper-busy”: On the other hand, many people have money, but no time. Rushing from job to job, chore to chore, task to task, social event to social event; with no time to really play and explore. Drowning in an “attention economy,” that competes for headspace and emotional bandwidth, those with money but no time tend to superficially traverse the city in Lyfts and Ubers—a big, gridded series of transit corridors, stations and airports.

The pandemic: Recently, however, there has been a major interruption to our usual flows. Between economic turmoil, the pandemic’s forcing of “non-essential workers” to stay at home, I think many of us have really been relating to time and space quite differently. And in this disruptive moment, I think it’s so telling that so many people with money and the flexibility to work remotely have opted to leave the city to go roleplay rural lifestyles in remote Airbnbs. The cities aren’t worth their time. But the pandemic has also caused many of us to wake up to the fact that the ideology of perpetual work is itself inherently flawed; that shoveling our living hours into the furnace of production is no way to live!

Technology and economic crisis: Of course, major changes have been taking shape well before the pandemic, and continue to take shape alongside the pandemic. As Andra mentioned, there are the technological innovations in artificial intelligence, low-cost networked sensors, and robotics, and all sorts of innovations in fabrication techniques. These offer the utopian potential of making the marginal cost of goods waaay lower, while at the same time threatening a dystopia of mass unemployment. At the same time, there has been a prolonged economic stagnation for large swaths of the population in de-industrializing, developed countries. For many people, the recession of 2008 had barely ended when the pandemic struck, and now it looks like we face another recession.

Universal basic income: In the face of these changes, there has been increasing interest in policies such as universal basic income as a means of ensuring the economic welfare of all people. The idea is not new, but suddenly it’s becoming a mainstream idea. Cynically, a universal basic income could just be a modest check that doesn’t make up for widespread loss of employment, or the cutting of public services. Not offering enough to live on, it could just prolong the current economic experiment with capitalism, by propping it up and easing the severity of its systemic failures. At their most pragmatic, such proposals imagine themselves as a mere “leg up” to help people to gain the prerequisite qualifications necessary to become useful in the formal employment economy, as well as a stimulus injection to that economy.

Fully-Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism: But such proposals also have a radical utopian dimension that begs the question of what society could be like if all production was automated, the material abundance produced was equitably distributed, and nobody worked (in the employment sense) at all. Here, everyone would be paid a living income, no matter what, meaning that nobody would need to work, whether they were unable, or just didn’t want to. Certain socialist thinkers have theorized such a society for almost a century, and there has been a recent bout of literature on the topic, and the evocative handle “Fully-Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism.” (if you want to read up on this literature, here are some places to start: Aaron Bastani, Fully-Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto; Kristin Ross, Communal Luxury: The Political Imaginary of the Paris Commune, "Chapter 2: Communal Luxury" [the last half of the chapter is the best bit]; Steven Shaviro, No Speed Limit: Three Essays on Accelerationism, "Chapter 3: Parasites on the Body of Capital"; Peter Frase, Four Futures: Life After Capitalism, "Chapter 1: Communism: Equality and Abundance"; it is also worth checking out the Situationist artist Constant's utopian urban city design "New Babylon," and some of the writing about it, which tried to picture a world of no work and all play.)

But what about the post-work city? And yet, as this political possibility is contemplated by more and more people, there has been no significant discussion of the way that our built environments would have to change to accommodate this change in the way that we spend our time, effort, and attention. What could cities be like, if you and I and everyone else weren’t working (or expected to work) all the time? We think this is a profound question to ask, and one that demands a lot of imagination. Today’s design and imagineering charrette is about exploring this possibility.

Aspirations guide behavior: Before we dive into some of the themes and prompts that can perhaps guide our imaginations in this charrette, I want to say something about the power of design, imagination, and envisioning alternatives to the current reality. Much of what we do is oriented by a desired future as its endpoint. Generally, this is a culturally-produced idea of the “good life” that serves as an aspirational compass for present decisions. In my country, this guiding vision has, for the last century or so, been the idea of the “American Dream”—a suburban consumer paradise built around the nuclear family, individual wealth and career success. This vision continues to determine so much of how Americans behave on a daily basis, from their educational choices, to their financial choices, to their romantic choices. So many behaviors are oriented by the goal of the American Dream.

From futurism to nostalgia: And yet, this vision is beginning to crumble. The belief that hard work will pay off, and lead to the American Dream is proving to b an illusion for millions and millions of people. Increasingly, this dream appears not on the horizon, but in the rear-view mirror. As Svetlana Boym says in her brilliant 2001 book, “The twentieth century began with a futuristic utopia and ended with nostalgia.” Increasingly, we speak of “returns”—on the right, there’s a nostalgia for a previously “great” America, and on the left, there is a nostalgia for the Keynesian economic policies of the New Deal and the Great Society. Both are backwards-looking, and both are delusional. There’s no going back.

Architects of the future: The engineer and futurist Buckminster Fuller famously said that “We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims.” With this charette, we hope to turn boldly toward the future, to imagine what cities could be like, precisely in order to update the aspirational visions that people use to orient their everyday actions. Here, we invite you to engage in what Carlo Ratti and Matthew Claudel call “futurecraft”—positing future scenarios, entertaining their consequences, and sharing these ideas widely to enable public conversation, debate, and imagination. Here, perhaps the discipline of “future studies” can serve as a guide, which explores not just technological innovation, but social innovation. It’s crucial to remember that while we may shape our cities, they, too, shape us. An architect of the future must therefore constantly be prepared to imagine not only how our cities and spaces can be different, but also how we, as the people living in them, can be different. How might daily life, relationships, aesthetics, life ambitions change, in a different built environment? How might we cease to be human in the familiar sense, and become post-human? Of course, we’re always already cyborgs; our tools are extensions of us, and we are extensions of our tools, with no rigorous way to think about one without the other. But when our tools become environments, we tend to start perceiving the dynamics that they encourage as nature. All of this is to say: in your explorations, we hope you won’t just design for the naturalized person of today—the inhabitant of industrious, work-oriented built environments. We hope you will design for a humanity that could be.

Prompts

There are a number of dimensions that one might consider when they imagine what the post-work city could be like. We have written a prompt for these dimensions. They are as follows:

Public spaces: What kinds of public spaces might exist in the place of offices and factories and stores that currently dominate the landscapes of our downtowns and central districts? What facilities and attractions might exist to occupy the time freed from work? How might people interact with the forms and functions of the city, and determine its uses?

Housing: What kinds of dwellings would people have in such a world? Would people even continue to have “homes,” in the traditional sense, or might they drift—either from fixed place to fixed place, or else become sort of “urban hunter-gatherers,” eating, sleeping, playing, etc., entirely in public spaces, never claiming these spaces as their own, because the entirety of urban space has become a “benevolent machine” that provides all of the material necessities, functionality, safety, comfort, and entertainment that the home once did?

Regional distribution of the population: Economic opportunity has been the key driver behind migration and settlement throughout history, and has been the primary determining factor behind why human settlements are located where they are. How would a non-work world alter the geographical distribution of humans? Would certain regions depopulate, and others grow? Would existing cities dissipate, as people became free of the economic tethers of employment binding them there, and sought to live in smaller conurbations and rural settings? On the other hand, would society perhaps move its entire population into concentrated megacities, as rural and peri-urban production ceased to require human involvement?

Infrastructure: How might infrastructure work in such a world? How, especially, would people and goods move around, and for what new purposes, for not for work and commerce? How might automated and de-commodified distribution infrastructures function? Would there be pilotless drone deliveries, pick-up points, and driverless ground transportation, as is already developing now? Or might a population freed from the time constraints of employment return to simpler methods of transportation and brick & mortar “shopping” for goods and necessities? What, moreover, might be done with the vast existing infrastructures of work and human-powered production (offices, factories, etc.).

Institutions: How might institutions function differently, and what kinds of formal/spatial conditions might this call for? How, for example, might education function in a post-work world where education no longer must be rushed into the early years of one’s life, to make time for work? How might the city accommodate alternative educational practices, perhaps with students of diverse ages and backgrounds? How might healthcare function? Government?

Care, friendship and socialization: A world without work is likely to be a world with more rich, complex, and considered social interaction. What might social spaces be like in such a world? How might people spend time together, meet new people, seek entertainment, conduct their sexual lives, etc., and what kinds of places might accommodate these activities? How would care (either supportive care for children, the elderly, the disabled, etc., and/or everyday care between people) function in a world where nobody has to work? What kinds of spaces might be set aside for these various types of care?

Time: How would time function in a society freed from work? Would we all continue to sleep primarily at night, and to move around during the day? Or would there be new kinds of nocturnal worlds, new kinds of 24-hour spaces, new explorations of what is possible and desirable at night? Relatedly, how might cities and their spaces relate to seasons differently? How, for example, might activities and spaces be designed to relate to seasonal changes in weather, climate and lighting conditions, where the productive city sought to defy these changes in order to keep the wheels of commerce moving? Might the city come to resemble seasonal resorts? Or might cities be altogether abandoned for a nomadic migration between seasonal resorts? At the scale of a lifetime, how might the removal of work lead to a reconfiguration of the way one organizes their lifespan—with career concerns typically dominating this organization—and how might this change the kinds of activities that cities are designed around (schools and play spaces for children, workplaces and entertainment-oriented leisure for adults, and eldercare and retirement activities for the elderly, etc.)?

Energy, food and waste/urban metabolisms: How might the organic metabolism of the city work in a post-work world? How would people participate in the capturing and use of energy? How might the interrelated management of food supply and waste be handled? Would humans become more or less involved in the capturing of energy, the production of their food and/or the disposal of their waste?

Creativity and aesthetics: Would there be a coherent or consistent aesthetic to the post-work city? How might art, design, music, and other forms of creative practice and production be accommodated? Might creativity shape and reshape the city on an ongoing basis?