In the last 24 hours, we have witnessed the erection of a so-called “autonomous zone” in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle, whose unofficial mantra has been described as “free food, free speech, and free of police” by the New York Times. The barricaded neighborhood has drawn the ire of President Trump, who threatened to take the neighborhood back from the “Domestic Terrorists” if the local and state authorities don’t do so first. “If you don’t do it, I will. This is not a game.” Trump demanded on his favorite social media platform. What the President doesn’t realize is that autonomous zones are a likely and logical response to a crisis of governance that he himself has precipitated.

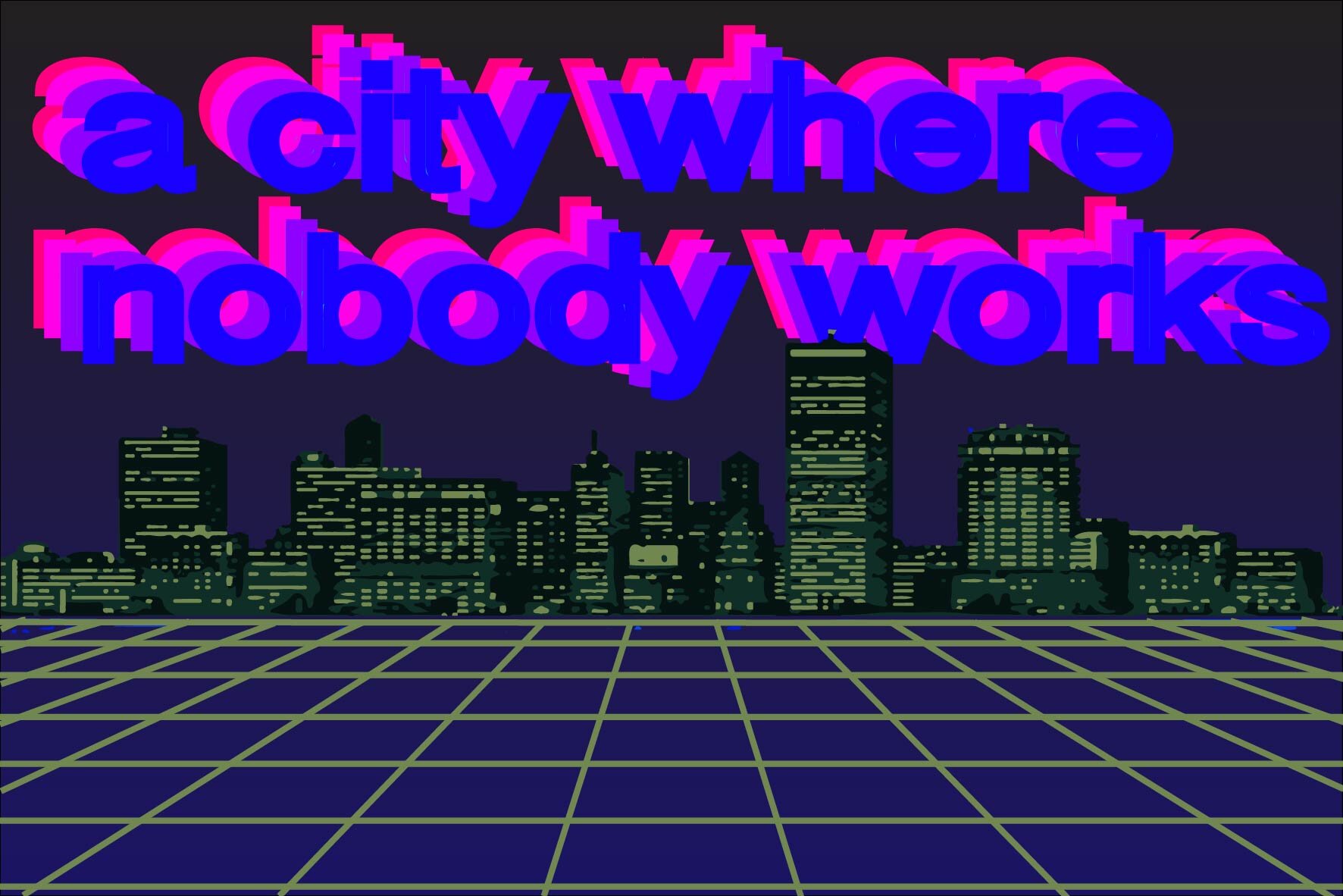

Autonomous zones have a long history (most notably in places such as Christiania, Marinaleda, Chiapas, Exarcheia, etc.), as movements have sought to challenge the governing bodies and paradigms of their respective societies. In a world in which all territory is occupied by hegemonic nation states who claim to be the sole authority, self-governance outside of the state is effectively banned, since the state maintains both a “monopoly of violence” and also enforces laws and ensures rights. Under present conditions, there is nowhere you can go to exist outside of police power, capitalist relations of production and exchange, or private property ownership. There is nowhere you can go to experiment with new kinds of public accountability and public safety, or new forms of property tenure and use, or new kinds of political decision-making.

Many might find the state’s hegemony tolerable, if that state (and the economic, social and cultural paradigms that it enforces, encourages and regulates) was doing a good job, but that is certainly not the case. Inequality, unaffordable housing, a variety of economic, social and medical epidemics, a breakdown of public services, a breakdown of social solidarity, pervasive racialized violence and environmental catastrophe—all of these threaten the stability, viability and legitimacy of our current government (and most of these have been in place for far longer than Trump’s presidency). At the same time, under present conditions of so-called “neoliberalism,” the government increasingly rejects its duty of care toward its citizens (as evidenced very clearly in the Coronavirus crisis, where the government essentially threw up its hands and said: “this isn’t our responsibility”). The result of all of this is a massive vacuum of governance that demands alternative solutions.

With this context, we should understand autonomous zones to be about much more than merely barring the police from entering. We must read the opening of these experimental spaces as a sign that existing governance and norms are failing to provide safety or the conditions for economic, social and/or creative flourishing. It is not just about eliminating governance and norms, therefore, but about experimenting with new governance and new norms that are better suited for safer, fairer, and more just ways of being. Autonomous zones are places where different kinds of governance and norms may be implemented—even if only temporarily.

What’s so powerful about these kinds of experiments is that they offer a glimpse into what the world could be like, if it was governed differently. They create the soil for new ideas and desires to take root. These experimental spaces, by giving rise—even in a brief or limited way—to new kinds of governance, norms, social relationships, solidarity, etc., shake us out of the crisis of imagination that causes us to believe that there really are no alternatives—a condition that the late Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism.” The economic geographer David Harvey has insists on the importance of “liminal social spaces of possibility where ‘something different’ is not only possible, but foundational,” and claims that this is always necessary as a precondition for broader social and political transformation. {Harvey, Rebel Cities, xvii.} By creating a temporary break from the status quo, people are empowered to “do, feel, sense, and come to articulate” another kind of reality in moments or bursts. These “irruptions” allow “disparate heterotopic groups [to] suddenly see, if only for a fleeting moment, the possibilities of collective action to create something radically different.” {xvii}

The temporality of autonomous zones is therefore very important to their overall trajectory. An autonomous zone may aspire to become a permanent fixture, or it may instead be instituted as what the anarchist theorist Hakim Bey called a “temporary autonomous zone.” As Bey explains, what is so powerful about temporary autonomous zones is that they can exist anywhere, without a lot of overhead. It is usually not necessary to fight the state or other hegemonic power structures tooth and nail (or to sell out and find ways to monetize the experiment in order to maintain it within a state-managed private property system and within the bounds of state authority) to hold on to them permanently. Moreover, it becomes less important to get governance and norms 100% right in a temporary autonomous zone, since their temporary erection does not lead to permanent, calcified structures whose potential flaws could persist indefinitely within the new social, cultural, economic and political spheres opened up. Finally, by making the zone temporary, the experiment is able to avoid the many kinds of exploitation, opportunism and corruption that are always a real risk when status quo governance and norms are suspended. It’s not that these factors cannot be overcome, but they each demand their own infrastructural solutions, which the people participating in a provisional experiment—maybe for the first time ever—may not be prepared to implement. By remaining ephemeral, the temporary autonomous zone is able to be relatively uncompromising in its idealism.

Permanent or not, the autonomous zone stands as a beacon for other experiments. It does not merely open the minds, hearts and imaginations of those who take part in it, but lays the groundwork and sets the precedent for other experiments—no matter how big or small. Even for those who were not there, the autonomous zone opens up a sense of possibility, a fidelity to which many practices may establish. Out of them, new “utopian” ideals can form in the imaginations of millions, and these, in turn, can serve as the basis of new kinds of demands on existing governments and institutions—effectively twisting their arms to have fidelity to the social possibilities opened up by the autonomous zone.

For too long, “revolution” has been imagined to be a kind of grand event—a kind of epic, singular struggle built on a unified platform on universal declarations. What autonomous zones remind us is that political, economic, social and cultural transformations must first take root in our imaginations—and that the first beachhead in the struggle to liberate our imaginations is in the collective appropriation of space and time for prefigurative experiments in what is possible. The “revolution” likely won’t occur in one fell, permanent swoop, but through the making of a thousand autonomous zones that establish collective life on a better foundation than that crumbling one that the state can no longer justify or defend.