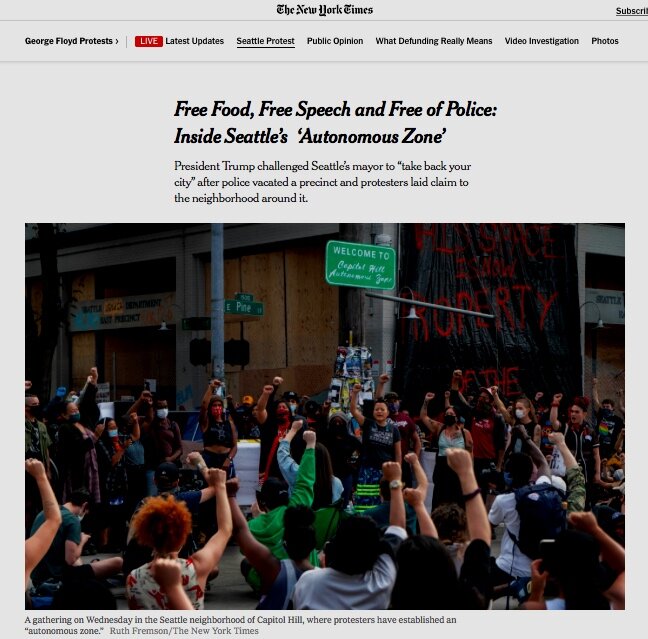

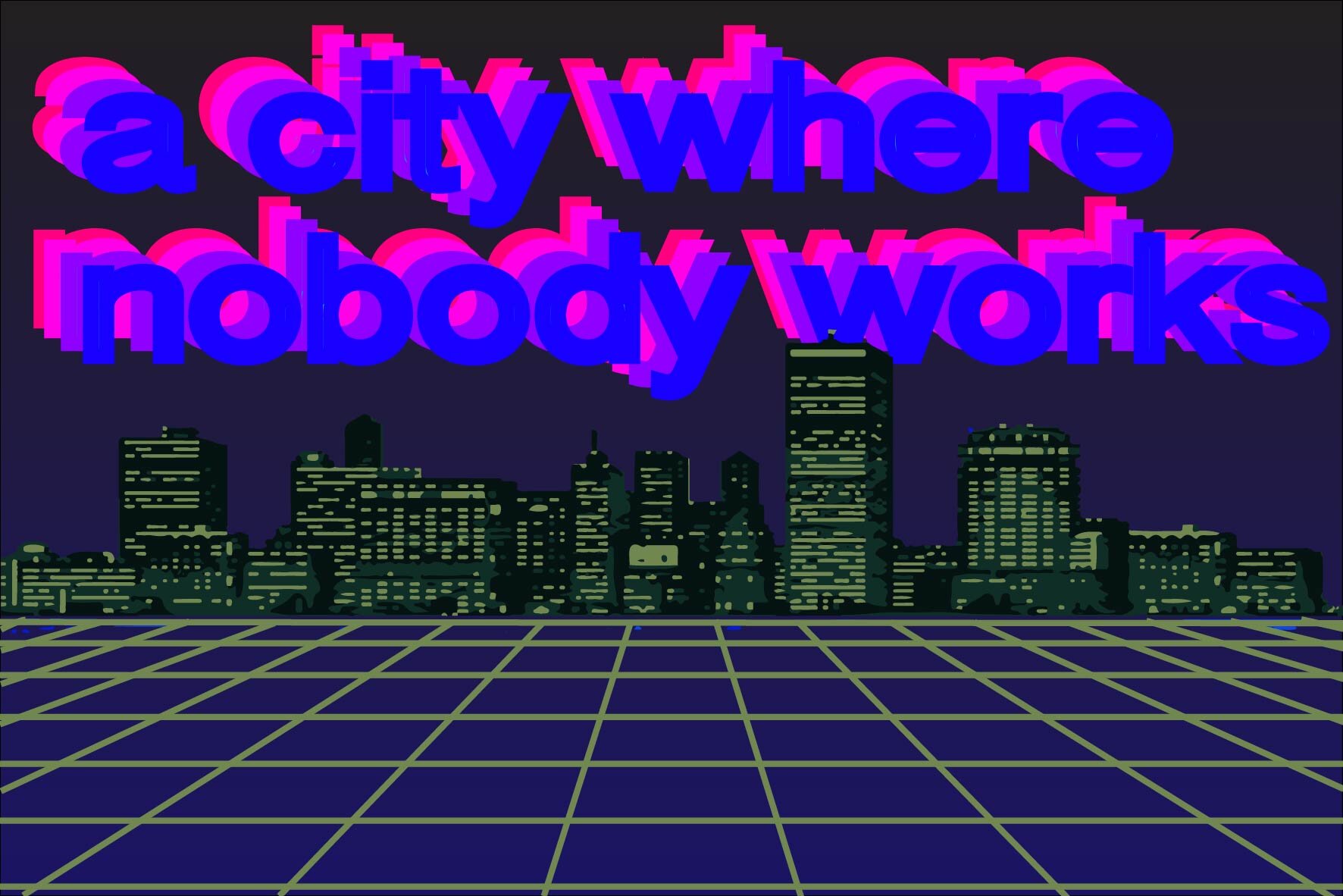

DISTROID is a subgenera of electronic music, arising out of an earlier branch of internet-based electronic music called “vaporwave.” Vaporwave takes the comforting noises and imagery of the 1990s and distorts it into a cheap veneer that simultaneously induces nostalgia, makes us aware--by making the interface between the past and present tangible (slowing down, static, record marks and other signals of retrograde reproduction technology)--of the past's ideological nature, and garners our disdain for the unfulfilled promises and abandoned hope of the pre-9/11 era. These elements and evocations (comfort and critique-via-contextualization) are something that the subgenera DISTROID separates out and holds in tension in distinct layers: on the one hand, the sounds and sights of the saccharine, “sugary onslaught” of popular music in 2018 (and this aesthetic, on its own, is accelerated and taken to its extreme by artists under the PC Music label), and on the other, the dark, dreary, tired, echoing mechanical sounds of disarray and degeneration (many of these having been pioneered and disseminated by dubstep and its predecessors).Vaporwave pioneered what might be thought of as an “anonymous subsidiary” production model of music, with digitally-veiled artists producing content under many different monikers, each deliciously named like a 90s product line, mall store, or bogus, patented chemical “technology” featured on a cleaning product (“SPF420;” “バーチャル Paragon ™;” “ECO VIRTUAL;” “R23X;” “waterfront dining;” “Windows 96,” “haircuts for men,” etc.). DISTROID continues to obscure the producer’s identity, but at the same time, it blurs the listener’s identity too. The clashing threads of comfort and critical contextualization are arranged in a way that leaves it unclear whether the creator made it for you, or for some AI observer who will use it as documentary evidence of how human governance and culture failed. DISTROID tracks feature unexpected cuts, often to thick, distant filtered sequences—blips, static, and interruptions. In this sense, DISTROID music sounds as if it is doing the double work of being musical for what’s left of humans, and also transmitting data for machines. It sounds as if data transmission is elbowing its way into the audio stream, reminding us of the saturation of transmissions between machines, as well as of the way in which we ourselves are increasingly hybridizing with machines. It thematizes the experience of little islands of comfort and joy in a dystopian sea of global chaos—a world that is out of our hands, and where people in positions of power run PR campaigns that insist that they are still in control of economic, political and technological processes, when in fact these processes dictate what people (especially the powerful) may do. Underneath the beeps, blips, and metallic file compression filters, DISTROID captures the atmosphere of chirpy advertisements playing in parallel on the gas pumps of an empty gas station; the cheap lighting of the freezer aisle; the endless empty analysis of the 24-hour news cycle; the out-of-order restroom; the narcissism on Instagram. It finds something drearily comfortable in its resignation to these familiar atmospheres. There’s something soothing in seeing the world in its actual form. DISTROID is the music of a world that uses its best technologies for porn and marketing and it is less industrious than distracted—cyborg music for a cyborg society in denial.

Writings

Featured

Incumbent Disadvantage