A few weeks ago, I posted, in a rather cavalier fashion, that I dislike spending time in nature. As the horrifying fires rage all along the west coast of the United States, I’d like to elaborate a bit on the ethics and aesthetics behind that post.

Ethics: If You Love Nature, Don't Live In It

First of all, let me just say that I love the earth, its geological and meteorological systems, its bountiful ecosystems, and all of the nonhuman life that we share our planet with. I think we should look after these systems, not only because they have intrinsic value independent of us, but also because we depend on these for our own survival.

But this love of the earth is not the same thing as an aesthetic love of being *in* natural spaces. Let’s remember: loggers and hunters and frontiersmen have all professed their own love being in nature. Not only is an aesthetic appreciation of being in nature not the same thing as loving the earth and its systems; a strong case can be made that the aesthetic appreciation of nature is actually exacerbating the crises plaguing the earth’s ecosystems, since it inspires humans to abandon cities and take up residence in rural and/or semi-rural settings.

The most pervasive example of this is suburbia. Suburbia is an unequivocally destructive type of conurbation whose appeal is located precisely in its pseudo-pastoral aesthetics (there’s the old joke that suburbia cuts down trees and names streets after them). And this is just as true for rural development. As human settlement sprawls outwards, it not only displaces and disrupts ecosystems; it also increases the carbon footprint attributable to transportation of goods and people over longer distances. Moreover, as the recent fires in California have demonstrated, the blurring of the boundaries between the built and “natural” environments has meant that naturally-occurring processes (such as the small fires that should ordinarily periodically clear out the accumulation of dead vegetation in places with wet winters and arid summers) have been interrupted, leading to greater crises and more serious habitat destruction.

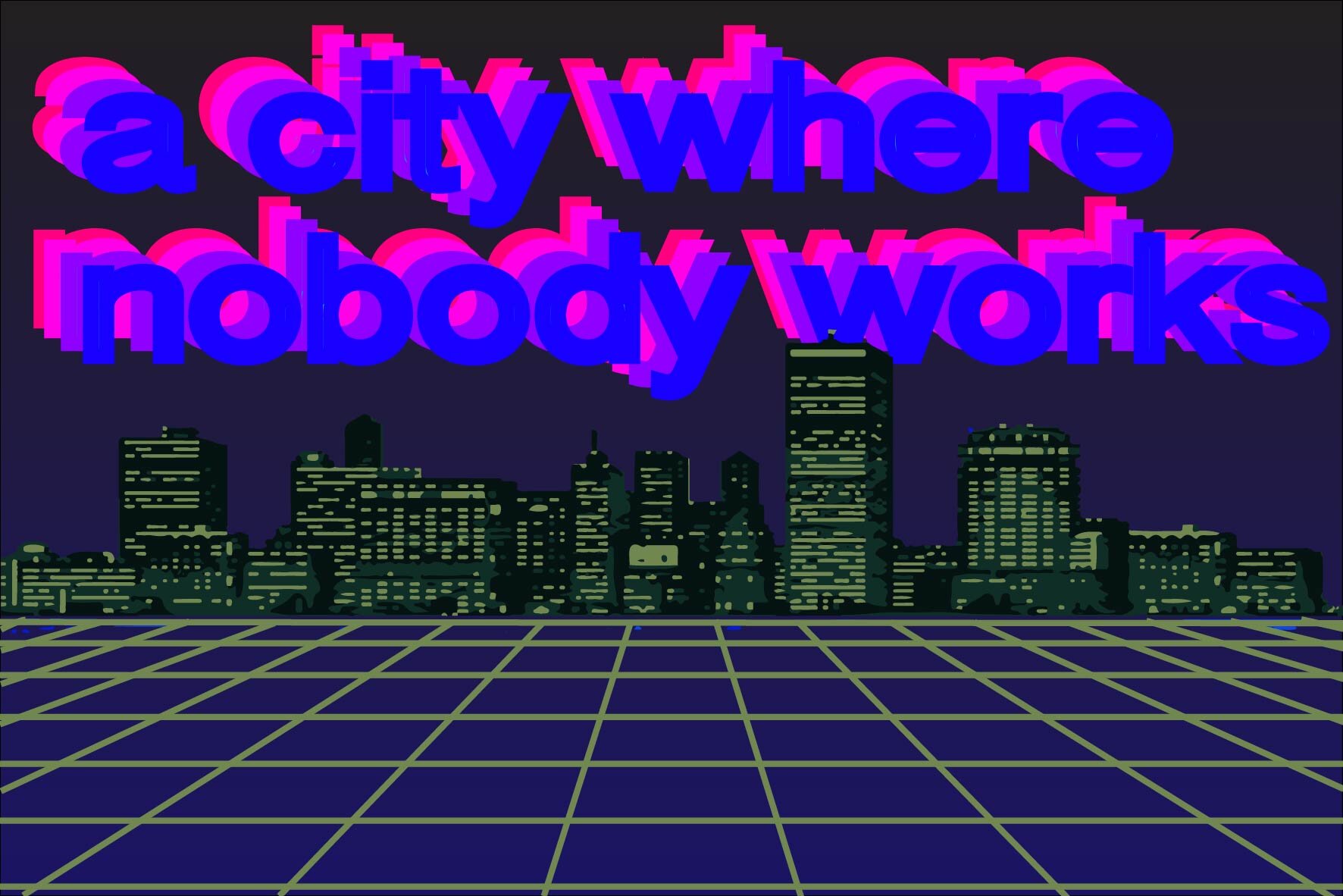

What would be much better is for there to be hard boundaries between urban and rural settings, with minimal infrastructural incursions into habitat. This would be the aim of a truly worthwhile preservation movement: clearly delineated cities, energy- and material-efficient lifestyles, and a re-wilding of rural land. Unfortunately, the trends are moving in the opposite direction (and this will probably be exacerbated by the lifestyle choices of the middle class in the wake of Covid)—most recent development in California has been occurring in fire-prone areas, and this trend is projected to continue, due to the pervasive affordability crisis in urban housing markets. But this is yet another reason for why we should be *solving* our urban affordability crisis, and making cities more interesting, beautiful and livable more generally. If you’re in a position to think about ethics (many people aren’t!), and you love nature, you might consider living in a city and leaving it alone.

But let me address another dimension of this issue: the very concept of nature is flawed. The concept of nature creates an artificial distinction between nature and human culture, as if the latter is not part of the former. To escape to nature is to fool oneself into thinking that they are escaping culture, as if the practice of aesthetically elevating and spending time in wilderness is not cultural or ideological (it is!). Perhaps even more perniciously—from an ecological perspective—is the fact that, as Benjamin Bratton has explained, this “nature/culture divide didn’t [even] protect what it called nature, even as it elevated the notion to a transcendental ideal.” Not only has this elevation of nature to a transcendental ideal not protected the sphere of activity we call nature; it has actively harmed it, in the ways I have already mentioned.

Aesthetics: Retreatism vs. ”architects of the future”

In my post, I stated that I specifically find spending time in nature to be boring. The implication was not to say that cities, by contrast, are particularly enjoyable. On the contrary, we've utterly failed, especially over the last 200 years, to build cities as places "fit for human habitation," to appropriate Hannah Arendt’s phrase. My aesthetic boredom with nature, then, is not a favoritism for “really-existing cities,” then, but for what cities could be. Our capabilities to make dreamy, complex, dynamic, labyrinthine, even sublime urban environments has never been greater. And yet, as a culture, we continue to foster a pervasive pastoralism and nostalgia in our aesthetics.

The love of nature aesthetics, in 2020, has a certain defeatism inherent to it. My worry is that the latest wave of nature-loverism is symptomatic of the abandonment of ambitious and audacious human bids to shape their own environments, because the built environments of late capitalism are so barren, sterile, dangerous, uncomfortable, and highly stratified. As Rem Koolhaas’s brilliant essay on “junkspace” makes deeply palpable, we’ve squandered the resources of the world, yet done so little of value with them. “Junkspace,” he says, “is the sum total of our current achievement; we have built more than all previous generations together, but somehow we do not register on the same scales. We do not leave pyramids.” What we have instead is “a low-grade purgatory,” an “ornamental afterthought on hurriedly erected superblocks,” “flamboyant yet unremarkable,” built of lightweight and impermanent materials, and crisscrossed with traffic-congested highways. In addition to this, our digital cities have also proven themselves to be a dystopia of misinformation, Twitter mobs, scams, targeted advertising, status posturing, and an endless news cycle of horrors. In the face of all of this, many have elected to retreat into a conservative/primitive therapeutic "returning" to the land, rather than engaging in a direct confrontation with society’s problems.

It’s very understandable that people would desire a kind of escapism from the terrifying world of pandemics, high-fructose politics, asinine crowd behaviors, and all the rest of it. But that escape doesn’t necessarily have to be the (colonially-constructed) aesthetic category of nature. Personally, I prefer the realm of utopian projection, fiction, and design. Rather than backing out of our crises, I want to find a way forward—up and over the horrors of contemporary life. To contradict the common sense of a generation of disenchanted members of contemporary society, I would posit that perhaps our problem is not that our lives are too artificial and too disconnected from nature; perhaps, instead, the problem is that they are not artificial enough. Inhering in this idea is a wilderness far vaster than all the Yosemites and Yellowstones and Grand Canyons, with infinite aesthetic experiences to be had, and infinite versions of ourselves and our society to perform. Here, I stand firmly with Buckminster Fuller, who said that “We are called to be the architects of the future, not its victims.”